The invasion of Ukraine by the Russian military on February 24th caused an increase in equity and fixed income market volatility during the first quarter. The S & P 500 was down nearly 5% during the quarter and the Aggregate Bond Index was also down, declining nearly 6%. Market volatility also caused significant extremes in relative performance: Small Cap Value (+0.8%) vs. Large Cap Growth (-12.8%). Short-term Bonds (-2.5%) vs Long-term Bonds (-10.6%). Energy stocks (+39%) vs Technology Stocks (-8%). Precious metals were up (Gold +6%, Silver +6%) driven mostly by the Russian invasion which also drove the broad Commodities index up 32%. With geopolitical risk rising and the global economic picture becoming uncertain, volatility should remain elevated.

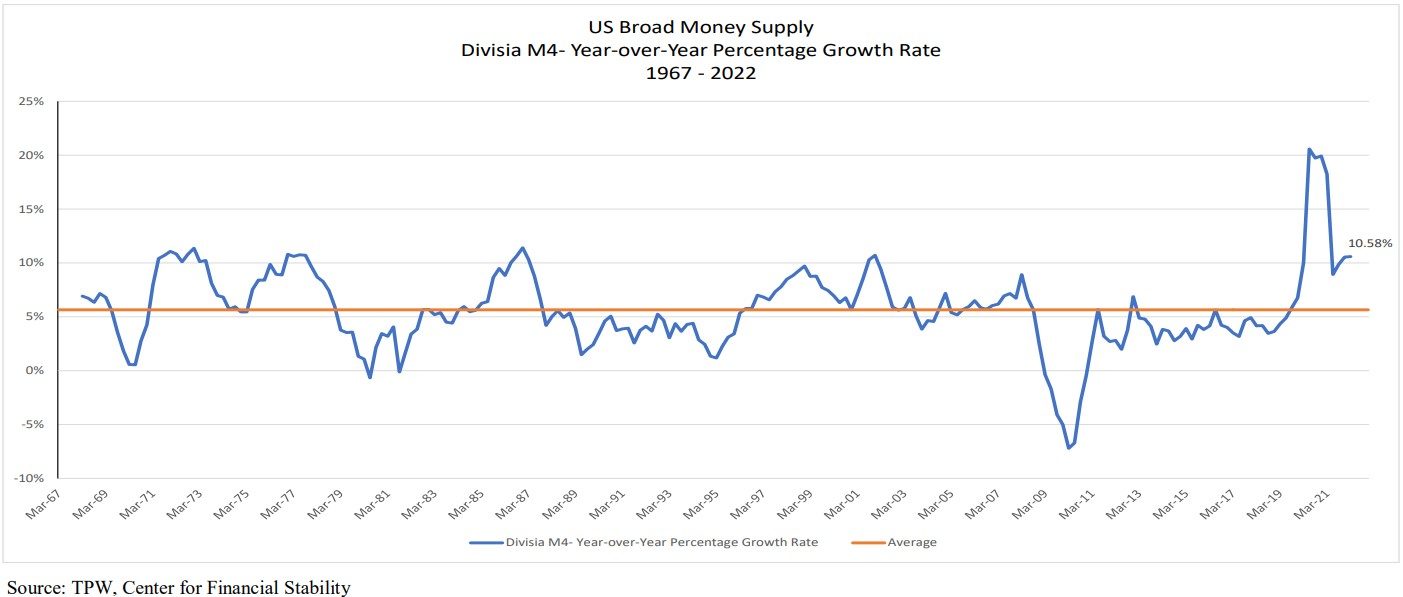

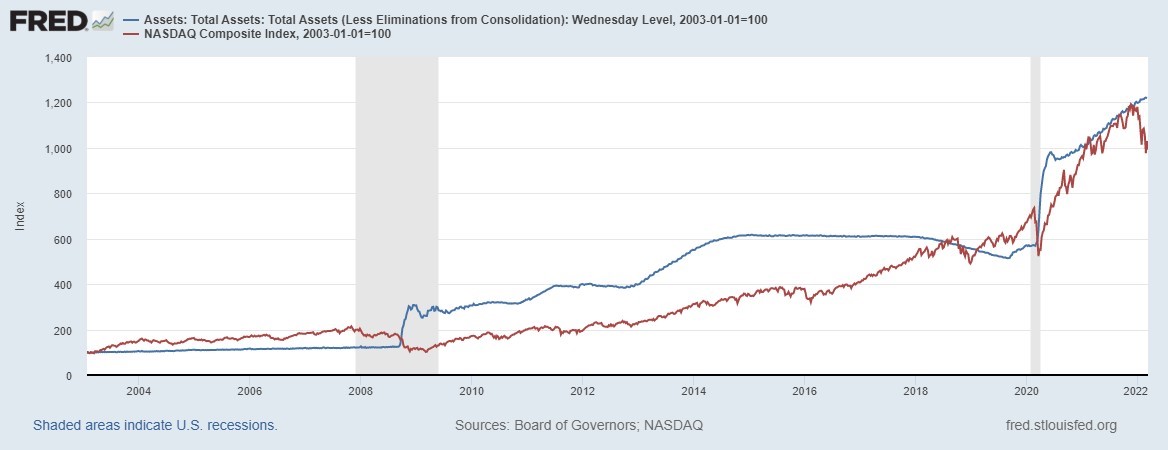

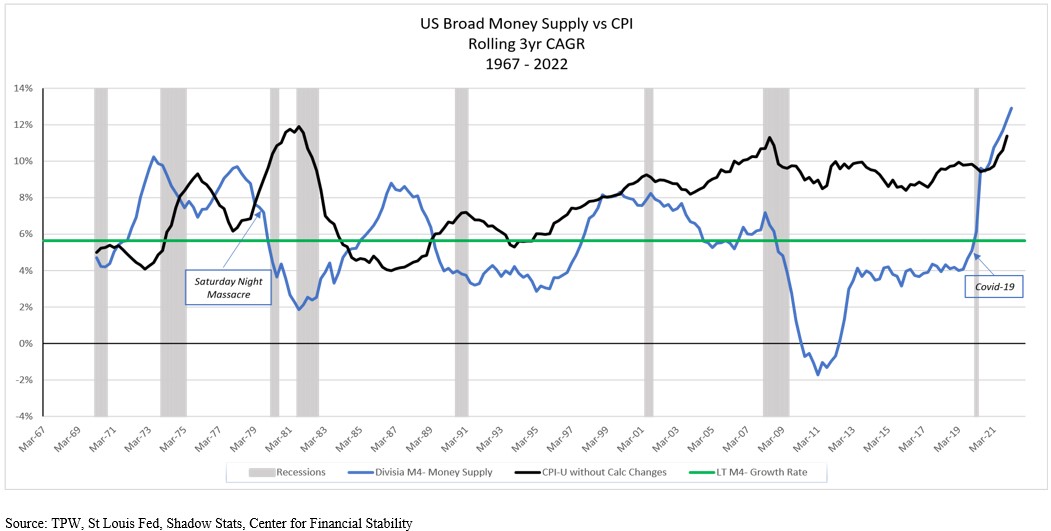

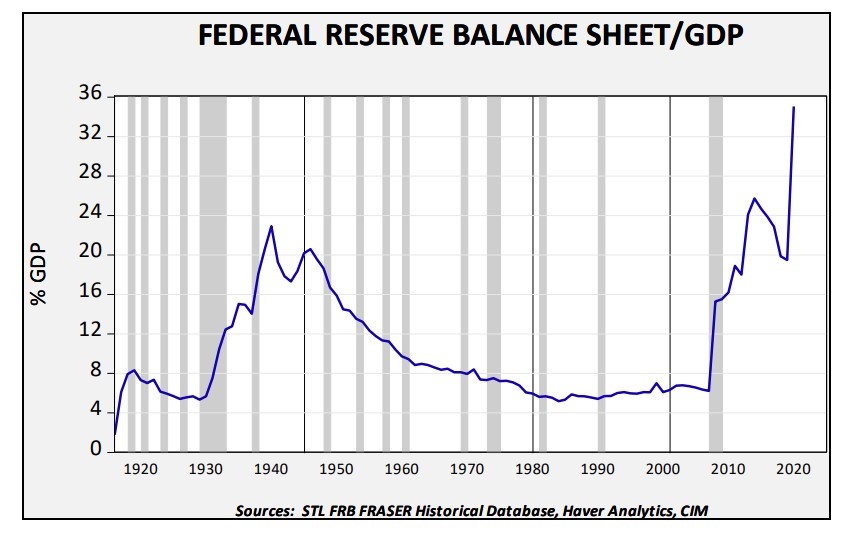

When not watching footage of the war in Eastern Europe, the markets remain fixated on the path of interest rates as determined by Chairman Powell and the Federal Reserve. Powell has finally acknowledged that inflation in the United States is a problem, as evidenced by the most recent Consumer Price Index recording a 7.9% year-over-year gain in February. To that end, the Federal Reserve raised the Federal Funds Rate at their most recent meeting on March 16th by 25 basis points or 0.25%. However, in a counterproductive move, they continued to increase the money supply – which grew nearly 11% year-over-year in January (Chart 1) by continuing to expand the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet1 (Chart 2).

Chart 1:

Chart 2:

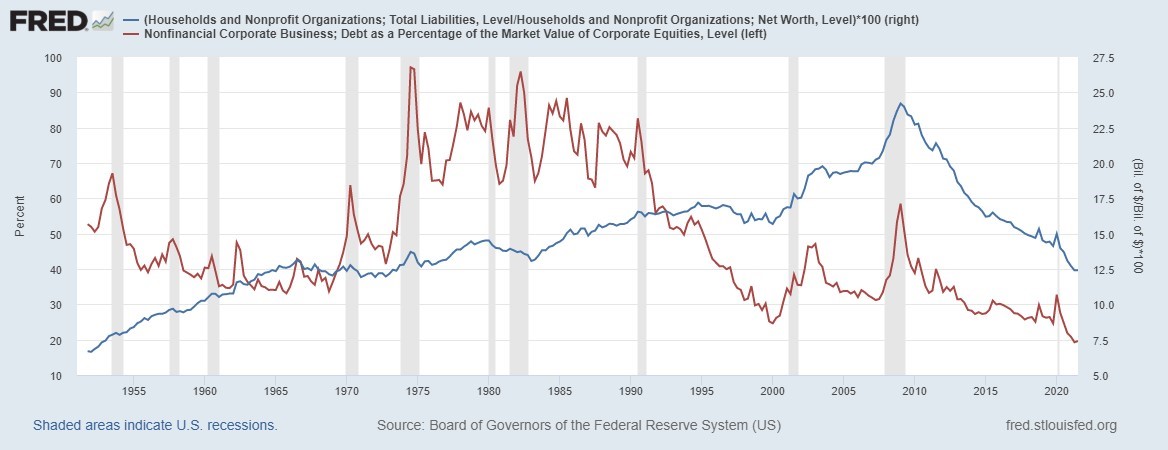

The Federal Reserve is attempting to engineer a “soft-landing” of the economy in order to quell inflation with its gradual approach to raising interest rates while the media continues to compare current conditions to those of the mid to late 1970s. The problem, as I see it, is that we are not in the middle of a debt-fueled economic boom. Unlike economic conditions during the 1970s and 1980s during which corporations leveraged their balance sheets, or the precursor to the 2008 Financial Crisis when both consumers and corporations leveraged their balance sheets – our current economic growth is being fueled by an excess in money supply growth and the wealth effect (estimated to exceed $1T) created by pandemic support payments, equity market returns (Chart 2 above: 2020-2021) and the boom in real estate. As you can see in Chart 3 below – consumer and corporate liabilities as a percent of net worth are at their lowest levels in 60 years.

Chart 3:

So how did the problem get fixed in the late 1970s?

Have you ever heard of the “Saturday Night Massacre?”

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter nominated Federal Reserve Chairman G. William Miller as Treasury Secretary as part of a larger cabinet shakeup. Miller, who had served a little more than a year at the Fed, oversaw a period of slow growth and high inflation—more popularly known as “stagflation.” In a move that signaled the growing discontent with inflation, Carter nominated New York Fed President Paul Volcker to take Miller’s place as Federal Reserve System chairman. Since the late 1960s, the nation had experienced a trend of rising prices as inflation began creeping upward from annual rates that were previously less than 2 percent for several years. In 1973, the Federal Reserve tightened policy to address an increase in inflation rates. However, in the face of higher unemployment, the Fed eased its policy before inflation had been fully

contained. The year-over-year inflation rate bottomed out at 5 percent in December 1976 before moving higher once again. By January 1979, inflation was threatening to rise further, as prices jumped 7.7 percent from the year before. During Volcker’s confirmation hearing in July 1979 before the Senate Banking Committee, the soon-to-be Fed chairman made his intentions clear. By then, inflation was running at an annual pace of about 9 percent. Volcker pledged to make fighting inflation his top priority, telling lawmakers the Fed would “have to call the shots as we see them.” In response to questions about his views on the money supply, Volcker responded the supply had been “rising at a pretty good clip,” and there was no evidence the nation was “suffering grievously from a shortage of money” (Dow Jones News Service July 30, 1979). Throughout the late summer and early fall of 1979, the Federal Reserve under Volcker had begun pushing the federal funds rate slightly higher. At the same time, unemployment began rising to about 6 percent, a move that began making officials in the Carter administration nervous, according to media accounts at the time. An unnamed Treasury official told the Wall Street Journal in September that the Fed would be forced to cut interest rates once unemployment hit 7 percent, “because the unemployment rate will be too high and Congress isn’t willing to bear that burden.” However, some members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) remained concerned about the level of inflation, and Volcker made a dramatic move to attack the problem. During a rare press conference on the evening of October 6, 1979, the Saturday before Columbus Day, Volcker announced the results of an unscheduled FOMC meeting held earlier that day. In front of reporters who had rushed to cover the unexpected announcement, Volcker explained the FOMC would shift its focus to managing the volume of bank reserves in the system instead of trying to manage the day-to-day level of the federal funds rate. It was an approach that would lead to more fluctuation in rates and, Volcker hoped, rein in inflation. “By emphasizing the supply of reserves and constraining the growth of the money supply through the reserve mechanism, we think we can get firmer control over the growth in money supply in a shorter period of time,” Volcker told the assembled reporters. “But the other side of the coin is in supplying the reserve in that manner, the daily rate in the market…is apt to fluctuate over a wider range than had been the practice in recent years”. As a result of the new focus and the restrictive targets set for the money supply, the federal funds rate reached a record high of 20 percent in late 1980. Inflation peaked at 11.6 percent in March of the same year. Meanwhile, the new policy was also pushing the economy into a severe recession where, amid high interest rates, the jobless rate continued to rise and businesses experienced liquidity problems. With the economy now facing a recession, it is perhaps not surprising that the Fed came under widespread public criticism. Farmers protested at the Federal Reserve’s headquarters, and car dealers, who were especially affected by high interest rates, sent coffins containing the car keys of unsold vehicles. In the 1980 presidential election, Ronald Reagan defeated Carter. With the Fed in a position to play a crucial role in the success of the new administration, Reagan’s staff arranged a meeting between the new president and Volcker. A member of Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers noted on behalf of the administration that they recognized the Fed’s independence but that view was not held by everyone. With interest rates high in the Volcker-led fight on inflation, the attacks came from both political parties. “We are destroying the small businessman. We are destroying Middle America. We are destroying the American dream,” conservative Congressman George Hansen said during a 1981 hearing. During the same hearing, Texas Congressman Henry Gonzalez threatened to introduce a bill to impeach Volcker and most of the Fed’s other governors. By the summer of 1982, House Majority Leader James C. Wright Jr. was calling for Volcker’s resignation. Wright said he had met with Volcker eight times in hopes of giving the Fed chairman an “understanding” of what high interest rates were doing to the economy, but Volcker was apparently not getting the message. However, in July the data showed that the recession had bottomed out. Volcker told lawmakers that he was backing off his previous targets for tight monetary policy and that a recovery in the second half of the year – long touted and targeted by the Reagan administration – was “highly likely.” At the same time, after hitting its peak in 1980, inflation began to decline, falling to 6.1 percent in early 1982 and then to 3.7 percent in the following year. The unemployment rate hit a peak of 10.8 percent in late 1982 before beginning a steady decline. With the recovery at hand and inflation greatly reduced, the political pressure on Volcker and the Federal Reserve eased, and the economy entered a new period of sustained growth and low inflation. Prior to the dramatic announcement in October 1979, the Federal Reserve’s policies had produced high and variable inflation and contributed to macroeconomic instability. There was little confidence that inflation could rapidly be brought under control without enormous economic disruption. The prevailing strategy of gradualism had been to bring the inflation rate down slowly over time through fine-tuned adjustments in the federal funds rate. By breaking with traditional operating procedures, and persevering despite a recession that was quite large by historical standards, the Fed re-established credibility for low inflation. In the end, the recession turned out to be smaller than many gradualists had predicted. That credibility laid the groundwork for the long period of sustained growth, known as the Great Moderation, which lasted from 1985 to 2007. Economist Milton Friedman summed it up best when he wrote “The great monetary policy mistake of the late 1960s and 1970s was that the Fed pegged short-term rates while ignoring unhampered money growth, which essentially accommodated federal spending and deficits to finance the Great Society and the Vietnam War.”

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”

Chart 4 below takes the data from Chart 1 and smooths it by using a 3 year rolling average. The money supply needs to grow over time, at nearly a 6% Compound Annual Growth Rate, in order to support growth in the economy. Growth rates above or below this rate indicates the Federal Reserve is expanding or contracting the money supply. The period after the Saturday Night Massacre shows the success the Federal Reserve had in reducing inflation (the black line) by reducing the growth rate of money supply to approximately 2% after a long period of near 10% growth per year.

Chart 4:

Conversely, the significant contraction in money supply after the Financial Crisis of 2008 brought on a “jobless recovery” during the period from 2009 to 2018.

Chart 5 below provides a sense of scale to the problem facing the Federal Reserve by looking at the size of the Fed’s balance sheet as a percentage of our economy over the last 100+ years. The Fed has previously responded to economic crises by expanding their balance sheet, e.g. Great Depression, WWII, and had been on their way to unwinding the expansion that occurred in response to the ’08 Financial Crisis when Covid-19 hit – resulting in an all-time high for this measure at the end of 2021. The bottom line is that the Federal Reserve has a long way to go before it can get the genie of inflation back in the bottle.

Chart 5:

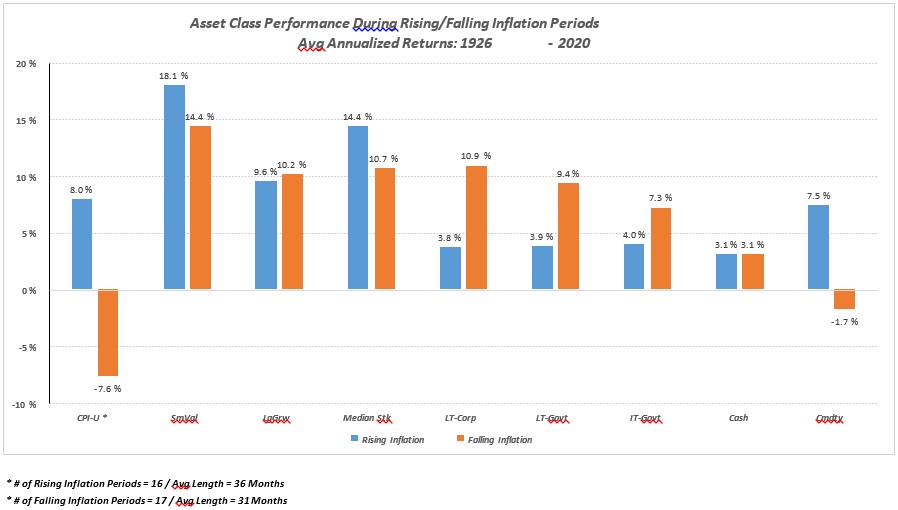

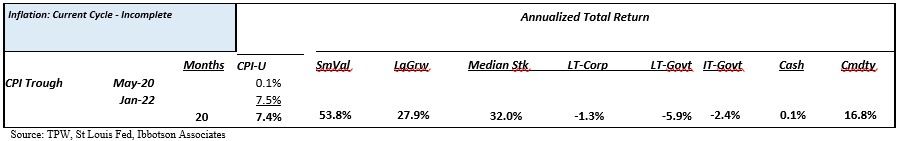

While we wait for the Fed to “Whip Inflation Now,” I thought it would be useful to look at how various asset classes have performed during prior inflationary periods. Chart 6 looks at both periods of rising and falling inflation over the last 95 years. There were 16 periods of rising inflation, averaging 36 months in length with inflation rising 8% over the period. The best inflation hedge has been small value stocks which we’ve discussed in prior letters while long-term bonds and cash were the worst at protecting your purchasing power. This current cycle, which started at the end of the two month Covid-19 recession of 2020, is about half way to the average cycle in length, with inflation already rising as much as the historical average. Remember, the Federal Reserve has just started to admit that inflation is a problem. The returns by asset class this cycle look very much like past cycles and, as we stated earlier in this letter, we see no reason to alter our portfolio positions at this time.

Chart 6:

We at Twelve Points Wealth hope you and your family are well and extend our thoughts and prayers to the people of Ukraine. Please call or email if you have any questions.

![]()

Steve Bruno, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

April 1, 2022

Disclaimer: Historical data is not a guarantee that any of the events described will occur or that any strategy will be successful.

Past performance is not indicative of future results. Returns and data cited above are from various sources including Factset, Bloomberg, Russell Associates, S&P Dow Jones, MSCI Inc., The St. Louis Federal Reserve and Factset, Inc. The content is developed from sources believed to be providing accurate information.

The information in this material is not intended as tax or legal advice. Please consult legal or tax professionals for specific information regarding your individual situation. The opinions expressed and material provided are for general information and should not be considered a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security. Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal. Please consider the investment objectives, risks, charges, and expenses of any security carefully before investing.

Twelve Points Wealth Management, LLC is an investment adviser located in Concord, Massachusetts. Twelve Points Wealth Management, LLC is registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Registration of an investment adviser does not imply any specific level of skill or training and does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by the Commission. Twelve Points Wealth Management, LLC only transacts business in states in which it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration.